Note: This report is also uploaded as a Word document File:Local content tot1.doc)

8-9 OCTOBER 2009

LOCAL CONTENT WORKSHOP

CAPA BUILDING

ROYAL MUSEUM FOR CENTRAL AFRICA

TERVUREN, BELGIUM

1. THURSDAY 8 OCTOBER 2009

1.1 Challenges faced by knowledge sharing

Participants divided into five groups. Each group focused on challenges faced by knowledge sharing in traditional communities.

Issues discussed in the different groups bear significant similarities, and can all be clustered as follows:

Transmission of knowledge over time

- Oral nature of local content: content is undocumented and easily lost

- Generational gaps: custodians of information are too old or dead

- Loss of context: the context which makes local content valuable can be lost

- Technological evolution: communities overly rely on technology to record knowledge which was once lived, remembered and passed down to younger generations

Cultural barriers

- Language barrier: different generations in the same community may not speak the same language; different communities do not speak the same language

- Reluctance to share: culture can constrain knowledge sharing, as knowledge is only made accessible to initiated individuals

Specificity of local content

- Local content is specific to a determined community and cannot be easily transferred over space and time

- Local content and traditional knowledge should be approached holistically: studying and documenting traditional medicine without references to local culture is wrong and can be counter-productive

Economic factors

- Intellectual property: those who own knowledge are reluctant to share it in order to maintain their competitive advantages (commercialisation of knowledge)

- Poverty: increased scarcity of resources and poverty make local content irrelevant in the short term and endanger its perpetuation and reproduction in the long term

- Demand for local content: certain forms of content are only required in the community that has generated them

Socio-psychological barriers

- Mindset: custodians of traditional knowledge are often socially and culturally marginalised, and develop a sense of inferiority

- Self-confidence: traditional communities and individuals often do not value their own experiences

- Perceptions of local content: traditional knowledge is now perceived as 'weird'

Costs and difficulties of collection

- Costs of collection: collecting local content is expensive; however, it needs to be done now rather than later, as costs will be even higher if no action is taken

- Methodology: how to collect local content is in itself an issue

External factors

- Government action: government action ignores local content, or documented traditional knowledge is not disseminated nor used widely

- Contact with Western culture and the heritage of colonialism: loss of confidence in traditional knowledge

- Contact with modernity: the 'human element' typical of traditional knowledge was suffocated by science and technology

- Media: local content is misrepresented in the media

- Lack of support by development work: development work does not favour knowledge sharing as a separate activity

2. FRIDAY 9 OCTOBER 2009 - MORNING

2.1 Reflections on first day

Participants were invited to reflect on the previous day and share the most valuable ideas discussed in both the formal exercise described above and informal conversations. These included:

- Local content can be used to solve problems towards development: it helps identify solutions to problems within a specific community; the solution can also be applied in other geographical and cultural areas (John);

- However, local content does not necessarily lead to development: e.g. the traditions that regulate what to do when a king or a chief dies in a particular community is local content; still, it does not lead to development (Edna);

- Validation issues: documentation of local content requires accurate cross-checking of different sources in order to avoid misrepresentations;

- Demand issues: is there a demand for local content across communities? How can demand of qualitative local content be promoted? (François)

- Ethical issues: can elements from a community's culture be 'sold'? If not, what should be the business model for the creation of incentives to share? (Binetou)

- Temporal dimensions of local content: while information is only valuable when new, knowledge is only valuable when old;

- Need for a clear definition of the different roles of access centres, information centres and knowledge centres: a classification was proposed by which access centres only provide infrastructure to access information (computers, internet access, etc.); information centres additionally provide packaged information to meet a specific community's needs; knowledge centres collect, structure, repackage and produce knowledge (Paul).

- Emerging gap between 'local content 1.0' and 'local content 2.0': until recently, collection and repackaging of local content reflected the developmental actors' agenda and focused primarily on health and education; currently, we observe a shift towards reflecting the preferences of local audiences, with increasing content being produced on employment and revenue opportunities, entertainment (François);

- Difficulties in reconciling local knowledge and research, especially in health and agriculture;

- Role of young people as knowledge brokers (Kemly).

2.2 A little taxonomy: where do we position ourselves?

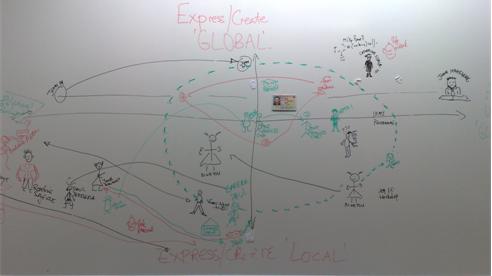

Participants were asked to position their activities on the chart below:

- John Mahegere is working for the Tanzanian Commission for Science and Technology. John's activities are diversified, and he found himself at home at different ends of the spectrum: as a manger of the Tanzanian government's programme for telecentres he would position himself towards the local content creation and consumption ends; however, as a liaison officer with international organisations, he is both a creator of content for global use and a consumer of global content.

- Jean Francise Asaba works for CABI, a bridging organisation which collects content, repackages it and disseminates it at all levels; at the same time, CABI also works with local communities to disseminate global knowledge; Jean Francise positioned herself at the intersection of the two axes;

- James positioned himself at the local content creation end: the approach chose by his organisation, ALIN, puts access centres and information centres at the heart of local communities: content is created locally for local consumption;

- Kemly Camacho Jiménew could not pin down her activities to a precise location on the chart: her organisation, Sula Batsá, is developing content locally, but use is not limited to the local level;

- Michael David positioned the activities of his organisation, Telnet.org (online radio and digital storytelling), at the local content development end: while the project is still at an experimental stage, development of content happens locally for a local Sri Lankan audience;

- Janet initially positioned herself at the local content creation end because her organisation creates content at community level using meetings, radio programmes, sms-technology and information centres; she later moved to the middle because she realised that, by making content available online and through audio-visual technologies, they also reach a wider, global audience;

- Felician Ncheye identified the role of his organisation at the local content creation end, because their activities at their knowledge centres are meant for the use of the local community: content is created at local level for local consumption;

- Deepthi's organisation manages an online database which, by definition, is geared towards global use; the database is however also made available on cds, which give wider access to it in many local communities in developing countries; content, on the other hand is both global and local; this is why she decided to position herself at the centre of the graph, facing global use;

- Catherine's organisation also manages a database, in this case collecting research; both creation and consumption happen at the global level, because research featured in the database comes from all over the world - although in reality most still comes from northern sources; Catherine is striving to connect to people who are closer to local content generation, so that the database can feature more local perspectives; her positioning is central, stretching hands to reach actors operating in different regions of the graph;

- Paul's organisation is a local creator and consumer of content, and chose to position himself at the local creation end of the graph;

- Roselinie uses content locally, validates information from the creators and disseminates it to the community. There after create the impact of the information thereby transforming information to knowledge as these will now be experiences of the community

2.3 The 'unblogged'

While most of the participants had already featured in the Local Content blog created by Pete Cranston, five had not yet, and were interviewed during the workshop.

2.3.1 Felician Ncheye: the Sengerema telecenter

Felician Ncheye is responsible for the Sengerema telecentre, in the Mwanza Region of Tanzania. The telecentre's mission consists in giving the local community a voice: content is collected or produced locally, repackaged, validated and shared.

"We have discovered that there are lots of resources within the community itself that can help development", Felician said. That is why he and his colleagues keep a particular lookout for all unrecorded knowledge and talent.

One of the thematic strengths at the centre is documentation on agriculture and agrarian techniques: adapting traditional knowledge from the centre, a cotton farmer from Sengerema has achieved 5 times the usual yield. The telecentre is also supporting farmers developing fish ponds.

Information is recorded and shared on cds and cassettes; best farmers are also invited to share their tips on a radio programme.

"The most important factor for a successful telecentre is widespread support in the community", Felician explained; "good management and relations with stakeholders are also key ingredients".

2.3.2 Binetou Diagne: the Africa Adapt network and climate change adaptation

Binetou is a young professional working on the Africa Adapt network. Africa Adapt is a bilingual (English/French) network of organisations fostering knowledge sharing on climate change adaptation. The founding partners are: Enda Tiers Monde, FARA (Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa), ICPAC (IGAD Climate Prediction and Applications Centre) and IDS (Institute of Development Studies).

"Local communities have already started adapting to global warming", Binetou said. Traditional knowledge and local content have always provided elementary tools to face climate change. These tools might however loose their effectiveness should the planet's temperature keep rising at the rates measured over the last two decades.

"As traditional climate adaptation techniques might soon become obsolete, it is important to bridge local knowledge and scientific knowledge in order to develop new strategies", Binetou explained.

Africa Adapt is doing exactly this: bringing together policymakers, local communities, research institutions, NGOs and the media to share knowledge and develop together new approaches to climate change adaptation.

At this stage Africa Adapt offers online services through a website; a radio programme in local languages is however soon to be launched in partnership with radio networks.

A fund for innovative projects to tackle climate change is also managed by Africa Adapt. In the course of 2009 the consortium issued two calls for proposals which met with extraordinary success: ca. 500 organisations have already submitted proposals. Funded projects must comply with high standards, including cultural and social parameters (e.g. use of local languages; inclusion of women and minorities).

2.3.3 Michael David: Telradio.org

Michael David is one of the founders of Telradio.org, an online radio project which kicked off one year ago and, even if not yet fully launched, has already met with considerable success.

The primary objective is to create an online space for knowledge sharing, open to local communities (the site is available in English, Sinhala and Tamil): "Knowleedge is the ability to be free", explains Michael in the words of Rabindranath Tagore. The portal, however, does not have a single target group or thematic focus, but aims at being completely demand-driven: the team working on it will allow the website to develop on its own as much as possible.

The philosophy behind the project is particularly fascinating: "We don't look at expectations; we look for the unexpected. We don't look at success; we look for challenges", concludes Michael.

2.3.4 John Mahegere and the Tanzanian Commission for Science and Technology

John Mahegere works for the Tanzanian government's Commission for Science and Technology, and is responsible for a governmental project aiming at creating a telecentre in each one of the country's 114. districts.

The project is facilitating development of infrastructure as well as managerial skills and capabilities in the population.

2.3.5 Kemly Camacho Jiménez: Sula Batsá

Kemly Camacho Jiménez works for Sula Batsá, a Costa Rican cooperative founded in 2005 by a group of professionals in knowledge exchange and ICT who firmly believe in the positive impact that ICT instruments can have on social work.

Sulá Batsá seeks to contribute to social change through creative work and creation of open spaces for knowledge exchange. Their activities aim to support and strengthen the work of other non-governmental organisations in Central and South America.

One of the organisation's main activities consists in the documentation of local histories. Sula Batsu trains young people and women from the interested communities to use audio-visual techniques and the internet; these skills are used to collect and document the community's own history. Around fifteen people are trained in each community every year.

The project's goals include development of skills as well as enhancement of a sense of identity and self-esteem for the local communities.

3. FRIDAY 9 OCTOBER 2009 - AFTERNOON

3.1 The Royal Museum of Central Africa: reactions

During lunch-break, participants were given access to the Belgian Royal Museum of Central Africa. These reactions were collected after the visit:

- Belgians have been extremely good at collecting content globally;

- Edna found that masks in the museum are similar to masks at home; but in the museum the setting makes them more attractive;

- The single pieces (masks) might not be as interesting as the whole exhibition (the exhibition is more than the sum of the exhibits);

- The museum has much to tell us about the way Africa is 'consumed' and perceived by average Belgians: the museum reinforces an image of Africa as primitive, remote, something you cannot and do not want to identify with; moreover, exhibits are out of context and 'lifeless'; on the positive side, attempts have been made over the last decade to put exhibits into a wider context, following the example of the Tropical Museum in Amsterdam (François).

3.2 What next? - Continuing work on local content

Participants divided into two groups to discuss:

- Echoes and ripples: efficiency of local content across space and time; demonstrating the value of local content;

- Suggestions for the recently launched African Knowledge Network (AKN).

3.2.1 Echoes and ripples: how to throw stones into the pool and create positive ripples?

The first group discussed how actors working on local knowledge can create positive ripples across space and time, making other actors aware of the possibilities offered by local content. Three forms of ripples were identified:

a. Formal collection and presentation of knowledge at different levels

This is arguably the most traditional way of creating echoes or ripples: collecting and document information, packaging and presenting it to a different audience.

The process is however not free of risks, as transfer can change the nature of knowledge and application of knowledge in a context different to its original can be ineffective or even counter-productive.

Moreover, there are numerous instances of deliberate distortion, of experience used as evidence even if not pertinent, of misunderstandings, misinterpretations or misquoting.

There are significant disincentives to sharing knowledge with others and using other communities' knowledge: this is why it is necessary to encourage co-construction of knowledge instead of mere extraction.

Central to the issue of reliability of information is its traceability: recognition of all actors involved in the transmission of local content as well as in the production of new knowledge must be explicit. Acknowledging the source shows appreciation for it and makes it accountable.

The promotion of local content should also focus on the added value local content can bring: in Africa there is untapped knowledge which can produce business (for profit, non-profit).

b. Echoes over space and time

Knowledge unused for years can resurface in different regions. The process is completely unpredictable, but frequent and therefore a significant factor in the propagation of local content.

Some examples were discussed in the group:

- The art of building traditional fridges with clay and charcoal had almost completely disappeared; it has recently spread across borders in Eastern Africa, helping farmers making the most of their dairy production and giving them easier access to urban markets;

- Research on improving vanilla production published twenty years ago has been re-discovered and used by farmers only recently, as producing vanilla has become exceptionally profitable;

- A traditional method to remove caterpillars from orange sweet potatoes has recently been re-discovered, and is being made popular through telephone assistance.

c. Events and Knowledge Fairs

Knowledge fairs are events where particular knowledge used so far to face local challenges is made available to other communities. Sharing and exchange are at the heart of the event.

The first international knowledge fair took place in Rome earlier this year (April). However, such events have existed for at least half a decade in Africa, where they are organised by local authorities.

Participants must be given strong incentives to share; this can be done for instance by means of a competition among participants to determine who is to host the next event (which, in turn, brings in revenue).

There are instances of farmers who met at a fair and started exchanging information and cooperating while based 200 miles apart.

Documentation of fairs must be accurate and comprehensive; media coverage ensures higher impact.

Moreover, value-added initiatives such as knowledge fairs are especially appreciated by donors and can help attracting extra funding.

3.2.2 Recommendations for AKN

The African Knowledge Network (AKN) is an initiative led by UNECA to transform access points into knowledge centres. The initiative will involve actors at local, national, regional and global level.

The initiative is based on a three-pillar structure, focusing on:

1. Content creation;

2. Building capability to generate content;

3. Ensure knowledge centres have required infrastructure to share knowledge.

Participants drafted a list of recommendations for the AKN board:

- AKN should define early in the project the exact scope of content to be covered;

- As telecentres cannot addres all content needs prioritisation is crucial;

- Partnerships should be built for content generation with the public sector, the private sector and civil society;

- Strategic resources should be clustered together in one centre, instead of multiple centres in the same locality;

- Consortia of content producers should be created at national level;

- Priority themes should be identified: regional portals should be organised thematically.

3.3 Reactions to the workshop

At the end of the workshop, feedback was collected around three main questions:

1. What was the most interesting for you?

2. What was missing?

3. What are you taking away and doing something with?

Participants particularly appreciated the opportunity to discuss the concept and the scope of what is understood under the label of local content. Better understanding which instruments are indicated for different audiences was also mentioned as an interesting and useful take-away from the tow-day session. Participants themselves with their experiences constituted possibly the most significant value in the workshop.

Regarding missing elements, participants mentioned in particular the lack of time, and, as a consequence, of content combination initiatives towards the propagation of local content throughout the African continent.